New device farm in town

Another day, another fraud.

With the holidays around the corner, you’d think fraudsters would take maybe a day or a week off. Instead, they are powering through, finding new ways to defraud the advertising industry with every chance they get.

Scalarr’s Analytics and Mobile Security teams discovered a new click farm operation consisting of two small and primitive mobile games that don’t have a large audience, yet they generate tons of impressions and clicks.

These apps share a common ID and publisher named Pitsos, which in some Eastern European languages may be translated as “Undersucker.” It’s only fitting that the name sounds like a wrestler from the WWE because these two small apps certainly pack a punch. It’s also fitting given the fact that it’s a click injection scheme.

The apps are called Fall and Fruits and they are both currently removed from the Google Play Store, but the iOS version is still available at the time this piece was written.

Figure 1: Google Play store page with install information for the Fall mobile app. Source: Google Play store.

Both apps are hard to search for and for example, the Fall app only has 1 installation (which is probably ours as we were doing research).

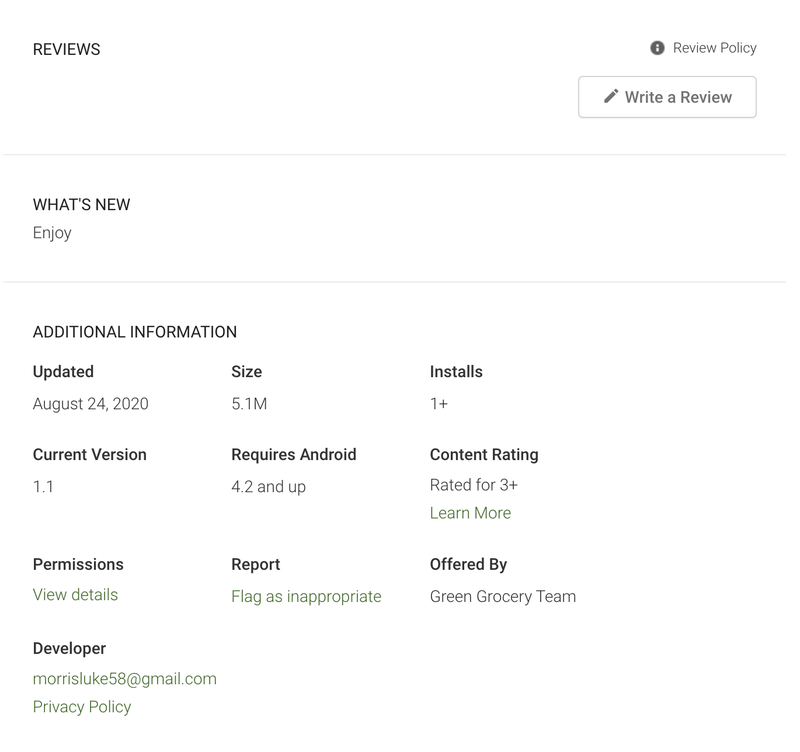

Figure 2: Details of the Fall app. Source: Google Play.

Without any reviews or comments, these apps have approximately 100 downloads each from the alternative storage Android Application Package (APK) combo.

Color us intrigued.

How Undersucker was found

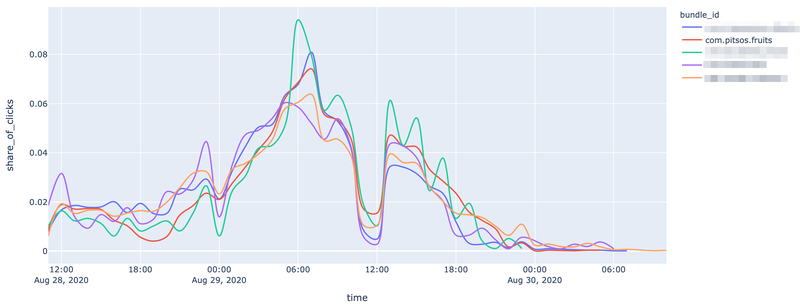

This Undersucker microfraud scheme was detected because of the mismatch between the high number of clicks these apps were receiving and the small number of users who installed the game in the Google Play store.

In the Fall app, over 8k clicks were recorded over a 2-day period. Weird for an app that only has 100 downloads, right?

Additionally, click patterns played a role as our Analytics team noticed that all click activity took place at around 6:00 a.m.

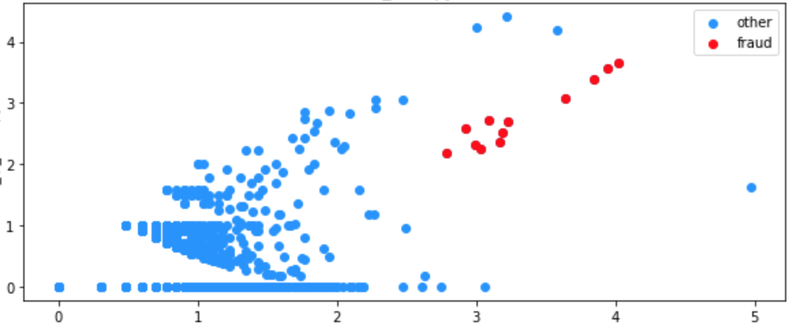

To prove the hypothesis of fraudulent activity, the Analytics team performed ML clustering analysis on these fishy apps and discovered a fraudulent group, as depicted in the images below.

Figure 3: Number of clicks versus the local time in-game for pitsos.fruits and other apps. Source: Scalarr’s Analytics team.

Figure 4: Clicks from different apps resulted in a separate click farm cluster. Source: Scalarr's Analytics team.

What’s inside the APK?

Android developers love their apps, as they should. They tend to follow the best practice of optimizing code and making the app compatible with the latest trends.

The APK for both of these apps was released on August 24, 2020, only consisting of an old HTML and JavaScript game inside.

Upon closer examination, this is what Scalarr’s Mobile Security team discovered:

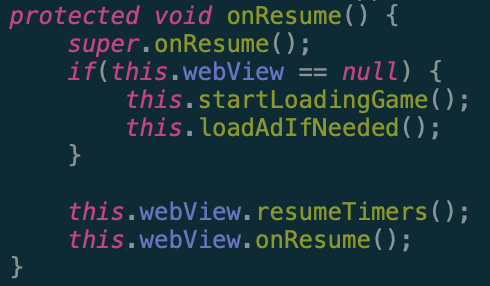

When the game resumed, the app called a method to actually start the game:

Figure 5: Extracted Java code configuring the application to load the game on resume. Source: Scalarr’s Mobile Security team.

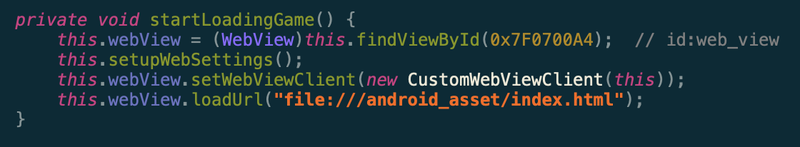

Inside this method, Scalarr’s Mobile Security team found that it only opened an index.html file from the Asset folder.

Figure 6: Extracted Java code loading the game from the Asset folder into a WebView container. Source: Scalarr’s Mobile Security team.

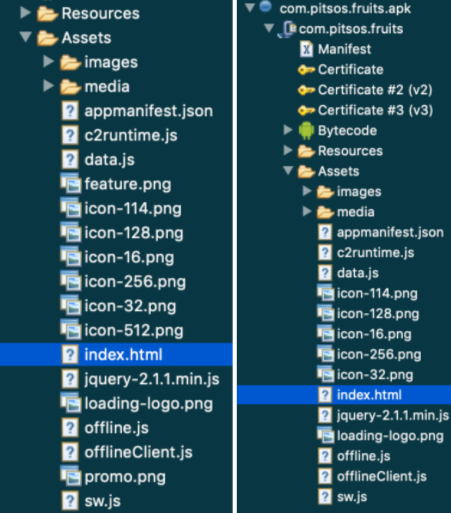

Inside the asset folder, there was a classical web game from 90-x. It only packed a WebViewer container inside with additional video ads preloading from mopub.

Figure 7: Extracted project structure for Fall and Fruits games, respectively. Source, Scalarr’s Mobile Security team.

Device farm galore

There was no malware code inside APK and these apps are deemed absolutely legal according to the Google Play Store terms and conditions. Regardless, these apps are useless in terms of value to the users and advertisers.

The simplicity of the game is an attractive lure for click farm automation. These apps are very convenient to use by device farmers since they only need to control one action.

Interestingly enough, by injecting a small number of fraudulent impressions per day, let’s say 1000 to 10,000, these apps could easily fly under the radar for a long period of time and not get any attention from ad tech vendors, advertisers, or ad networks.

The only solution for mobile advertisers is to partner with anti-fraud tools that make use of powerful and intelligent technologies such as machine...

The road to Scalarr's foundation was paved with challenges and opportunities and in this in-depth conversation, you'll learn the story of Scalarr f...